The 1st Independent Polish Parachute Brigade

(1 Samodzielna Brygada Spadochronowa)

Deportation To Archangelsk

On the 19th December 1939 the NKVD arrested me. Apparently I was "outspoken about Bolshevism", well, I wasn't going to accept their regime in my life, I wanted the Poland I loved not some foreign regime dictating to me how I should live.

They told me I was a "socially dangerous person" and as such would be deported to Archangel.

Well, the powers that be decided on the 27th of June 1940 that I would be sentenced to 8 years of hard labour in Archangelsk in Siberia. I had heard about these Gulags from my father, now, fate had decided I was going there too.

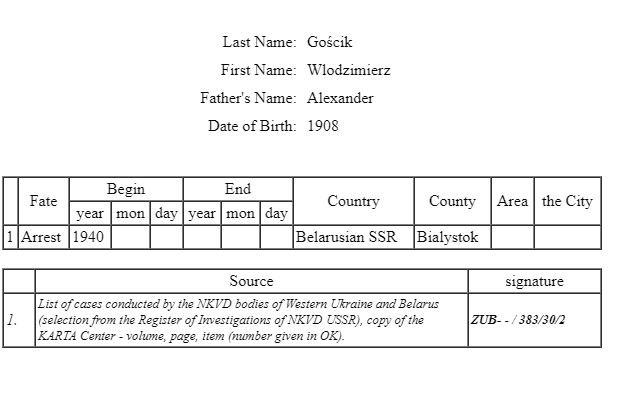

Here are the details from the "Index of The Repressed" of my arrest and deportation:

Well I had just heard that my entire family was being deported to Pawladarska in Kazakhstan, thousands of miles away and now me, to Siberia? What had we done to deserve this? My only crime, if it was a crime, was being Polish and hating this thing of Stalins called Bolshevism.

This man Stalin wanted to reduce all of us to peasants, not that I minded, being from a humble background, but a man should be allowed to work hard and enjoy the work of his hands without feeling he had committed a crime.

And so I was taken to the railway station with many other men. There was no refinery for us, a simple farmers dung cart pulled up and we were forced at gunpoint onto it. There was no point in trying to escape, the NKVD were only too happy to put a bullet in a Pole.

At the railway station we were ordered off the cart. Our papers were checked and re-checked. The train carriages awaited us, doors open. There was no going back, I knew what horrors lay before us because the older ones in Tarnowska, Bialystok the street where I lived with my entire family, told us of a time when members of their family had been deported.

We were forceably herded into a stinking cattle wagon with many other men. I was not fast enough and so an NKVD officer took it upon himself to club me over the head with a rifle butt. I hurried up, I had to stay alive, if not for me then for my family. At that moment, I knew I was going to be strong and try my best to survive.

And so we left Bialystok for Archangelsk in Siberia. My heart sank. I cried out, as did all the other men, we may have been brave soldiers of the Polish army fighting Germans just a few months ago, but we were mortal, we had feelings and we were powerless to fight now.

The train whistle rang out as we left Bialystok. We anxiously peered through cracks in the wood, desperate to see our beloved city. When would we see it again? None of us knew and we dared not voice this.

Soon cold set in, the steam off our breaths hung in the air. We had almost no food. Some soldiers had a few small rations and shared what they could, but it was not enough for one let alone the 46 men that were in the carriage.

The hours passed by and the natural functions of the body began. It started with men urinating on the floor, because there was nowhere to go. At first, other men would complain, it would splash on them and smell, before slowly being absorbed by the wood.

But as more and more men relieved themselves, we ceased to care, we were 46 men in a hellhole, this was the least of our problems.

And then it got worse. Men needed to do more than urinate. And so we came upon an idea to smash the floorboards in the middle of the carriage and make a hole..

Well, 46 men all taking turns soon managed to smash a hole in the floor and with great relief and massive embarrassment the first men started to answer the call of nature with the excrement falling on the railway sleepers below.

The strange thing is, pretty soon we did not care, we neither felt embarrassment nor held off answering the call

Through the cracks in the railway carriage we said our goodbyes to Poland and entered the world of the Soviet Union. The landscape changed, snow was thick and deep and the cold only got colder. We huddled together trying to keep warm as a group, but it did not work.

Every few days we would stop at a station and the engine would refuel. We would quickly run to the steam engine to get a cup or a pan of hot water with which we made weak tea.

Sometimes the train would leave the station hurriedly and sometimes the odd person was left there, in a very remote station. I cannot imagine they lived long, they were in the Soviet union and the Russians despised us Poles, spitting at us and swearing at us.

One night, Radek, a man in my carriage died during the night. We talked amongst ourselves trying to decide what to do with the body.

We had seen plenty of death, fighting the Germans in 1939, but for a fellow soldier to die in a locked, cold, Russian cattle cart is a travesty. The Russians will pay for this! I was angry, I liked this man, he told me about his life, his wife and his children and now he was dead.

At the next railway station we asked an NKVD man what to do with the body. He shrugged his shoulders and pointed at the railway siding just beyond the platform.

We buried Radek there by covering over his body with snow. Goodness knows what would happen to the body, would wolves get it? What about the thaw in spring, would the body become exposed and stink in the heat?

I shuddered and climbed back in to the railway carriage, my mind could not understand or compute these things.

Every day for 41 days we were in that railway carriage. Sometimes we were not moving, just sitting in a siding waiting for another locomotive to take us onward.

By now we all knew each others names and summaries of our lives, there was a camaradre amongst us, maybe we were just trying to block out the badness, the fear, the thoughts of our family and the horrors of Dantes inferno that awaited us in Archangel.

I was losing weight fast, I was beyond hunger, my belly ached, my legs no longer had feeling. Was I dying? I don't know, maybe we all were.

The coughing got louder and more drawn out everyday. More men died, some we passed through the hole in the floor, who knew what horrors awaited them when the next train passed over.

War, the Russians were hardening me. Things that used to shock me were now the norm. I drowned out the badness by thinking about my darling wife Stanislawa. Was it just a few years ago that I married her in Farna Parish in Bialystok? I walked her up the aisle and now we were both going down railway tracks, her to Pawlodarska In Kazakhstan and me to SevDvinLag in Archangelsk, Siberia.

Where was God? I asked this, the men asked this, where was our God? We were all Catholics, we lived with God in our lives everyday and yet where was he today? Had Stalin killed God? I thought so, because I could not understand why God would allow this.

My mind would wander to other questions such as how did Hitler and Stalin both manage to invade us in the same month? Had the 2 devils conspired together? No-one knew and yet it seemed so implausible that we could be dealt such a double blow of tragedy in such a short time.